I recently engaged with a client that wanted to improve their search relevance and speed. We decided to run some experiments to see if Elasticsearch would be a good fit.

Introduction

We wanted to be as visible as possible, and open for anyone interested to look at what we are doing. Many of the engineering team had not worked with Lucene based search engines before. I remember when I first used lucene, I felt pretty lost. So I threw together some lunch and learns and opened them up to everyone that wanted to pop by and learn the basics of Elasticsearch.

The deck that went with the workshop can be found here and there is a GitHub repo that will help spin up a single node instance and populate the search engine with some test data, written in C# & dotnet core.

The goal of this post is to cover the basic architecture of Elastisearch, in future posts I’ll dive into individual features (Like the search query DSL).

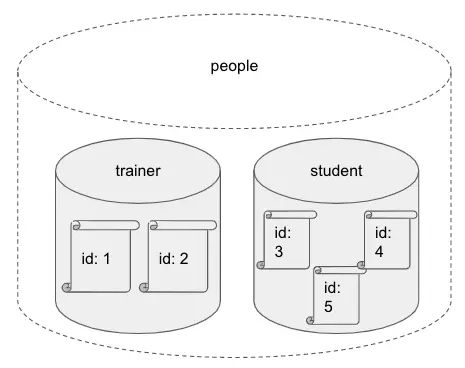

The running example of the workshop is a fictitious university consisting of trainers and students. For the purpose of this example we have split the index in this way, however depending on your usage you may decide to have a single index of people. It’s worth mapping out how you want your search engine to behave and change your data structure to match.

Also, modelling your data on how your users will use the systems is vital, in most cases the best search model will not be a mirror copy of your database models.

Elasticsearch

First off, its worth mentioning that Elasticsearch documentation is amazing. I hope to provide a brief overview, just enough to get going with Elasticsearch; go check out the docs once you’ve decided to make the jump.

So, what is Elasticsearch?

Simple put, Elasticsearch stores data, organises data and retrieves data.

To get started we can look a few of the key components that make up Elasticsearch

- Cluster

- (Types of) Nodes

- Indexes

- Shards

- Documents

- How to search

Cluster

So, let’s start at the top. The highest point in our architecture is the cluster.

A cluster is one of more nodes with the same cluster name.

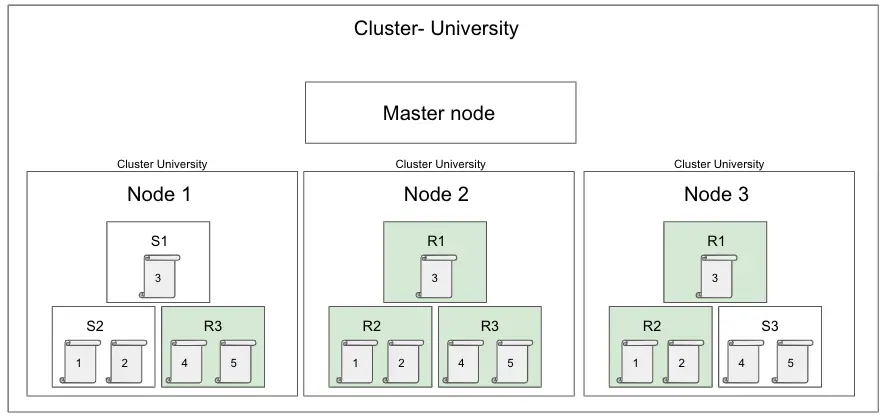

In this example we can see that our University cluster has a master node and 3 other nodes, all with some documents inside.

Nodes

But what’s a node?

Well, we have a few that I think everyone starting up should be aware of, and some that you can get back to later.

Nodes you should know about

- Data nodes

- Stores data and executes data-related operations such as search and aggregation

- Ingest nodes

- Apply an ingest pipeline to a document in order to transform and enrich the document before indexing

- With a heavy ingest load, it makes sense to use dedicated ingest nodes and to not include the ingest role from nodes that have the master or data roles.

- Master nodes

- Are in charge of cluster-wide management and configuration actions such as adding and removing nodes

- Client nodes

- Forwards cluster requests to the master node and data-related requests to data nodes

Other nodes

- Tribe nodes

- Act as a client node, performing read and write operations against all of the nodes in the cluster

- Machine learning nodes

- Available under Elastic’s Basic Licence that enables machine learning tasks.

Indexes

Within your nodes we have indexes, this is where you’ll find your documents. The index is the logical name which maps to one or more shards (more on this later).

We can explicitly create an index

PUT /trainer

{

"settings": {

"index": {

"number_of_shards": 3,

"number_of_replicas": 2

}

},

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"bio": { "type": "text" },

"subjects": { "type": "keyword" },

"name": { "type": "text" }

}

}

}

Or have Elasticsearch create an index when adding a document when it does not exist.

I find that if I create my indexes explicitly I have an easier time source controlling my configuration and replicating my configuration across many environments.

Querying index

We can query against a single index, alias or complete dataset by using the query DSL.

In this example we are searching our trainer index for a name that matches the query Matthew

POST /trainer/_search

{

"query": {

"match": {

"name": {

"query": "Matthew"

}

}

}

}

and expect the following return.

{

"took": 616,

"timed_out": false,

"_shards": {

"total": 1,

"successful": 1,

"skipped": 0,

"failed": 0

},

"hits": {

"total": {

"value": 1,

"relation": "eq"

},

"max_score": 5.9282455,

"hits": [

{

"_index": "trainer",

"_id": "1",

"_score": 5.9282455,

"_source": {

"name": "Matthew",

"startDate": "2020-11-1",

"interests": [

"Search",

"Baking"

],

"subjects": [

"Java",

"JS",

"C#",

"Elasticsearch"

]

}

}

]

}

}

Our response comes with some useful data, particularly

- took- How long our query took to run in ms.

- timed_out- whether Elasticsearch reached its configured timeout limit.

- hits-

- total- Information on the total number of results

- max_score- the maximum relevance score of the results

- nested hits- These are the results for the current page of results (defaulted to 10 results), they continue the index of the document, ID, relevance score and the _source (Or document)

Index alias

At our fictitious university we have trainers and students, however we want to search across people. An index alias is a simple way to make these queries easy to write and maintain.

POST /_aliases

{

"actions": [

{

"add": {

"index": "trainer",

"alias": "people"

}

},

{

"add": {

"index": "student",

"alias": "people"

}

}

]

}

We can now use the people index in the same way as our trainer and student indexes.

Shards

Each shard is a single Lucene (Open source Core search library Written in Java) index. These are automatically managed by Elasticsearch. We can configure primary and replica count, documents are then placed in random nodes across the cluster. Our indexes are split into 5 shards by default The rest should just work itself out

Replica shards

Used when primary fails, they should never be on the same node as the primary shard. Shards give us an increase in search performance and resilence.

- In this example our primary shards are labelled S1 (on Node 1), S2 (on Node 2), S3 (on Node 3).

- Collectively they contain all the documents, with the ID 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

- These are spread over multiple nodes.

- In this example we have 2 replicas, labelled R1 (on Node 2 and 3), R2 (on Node 2 and 3 ), R3 (on Node 1 and 2).

- The replica contains a copy of each document.

- And each replica is never on the same node as the primary shard.

Documents

A document is a record of data, they are stored as JSON (Key value pairs).

We can add this into our search engine by using the REST API.

PUT trainer/_doc/1

{

"name": "Matthew",

"startDate": "2020-11-1",

"interests": ["Search", "Baking"],

"subjects": ["Java", "JS", "C#", "Elasticsearch"]

}

In this example we are adding our trainer to the trainer index (more on this later) and an ID of 1. The body of this request contains the document that we want to index and search over.

If we then retrieve this document using we are returned the document and some extra information.

GET trainer/_doc/1

Returns

{

"_index": "trainer",

"_id": "1",

"_version": 1,

"_seq_no": 1,

"_primary_term": 1,

"found": true,

"_source": {

"name": "Matthew",

"startDate": "2020-11-1",

"interests": [

"Search",

"Baking"

],

"subjects": [

"Java",

"JS",

"C#",

"Elasticsearch"

]

}

}

The document is then returned with extra information- the ones I find the most useful being

- _index

- _id

- _version

- _seq_no

- _source

Creating a document

ID

Identifier of our document ES will generate these when omitted. Personally in most cases I prefer to supply my own ID, I find it much easier to keep my search engine up to date when my document is updated.

Field

We have a few different ways to store data including

- lists

- dates

- numbers

- booleans

- ranges

What if my data is complex?

Sometimes our data is much more complex than what the basic fields can accomodate for. We have a few different methods for storing more complex data structures.

These methods all have a use, however they also all have drawbacks. It’s important to think about what type would be best for your use case for each field. The cleaner your data is going in, the easier it will be to search later. When populating our search engine it helps to think about the value the engine will produce and how searches will be performed.

Object

The simplest form of our complex data structures is simply a single object.

In this example we have split our name into its own object of parts.

{

"name": {

"first": "Matthew",

"last": "Worthington"

}

}

These will then be flattened when stored like this

{

"name.first": "Matthew",

"name.last": "Worthington"

}

We can then setup a mapping for this object

PUT trainer

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"first": { "type": "text" },

"last": { "type": "text" }

}

}

}

Note that we do not need to set the type as this is defaulted to object

Nested

We may want to store an array of objects. Our trainers have an array of lessons, each lesson is an object holding basic information.

{

"name": "Matthew",

"lessons": [

{

"name": "Super amazing session",

"description": "Dolorem non voluptatem odio maiores minus. Amet nisi est recusandae veniam quasi maxime. Natus alias pariatur eos magni. Hic quo ipsa suscipit voluptas magni Pascal nobis et rerum. "

},

{

"name": "Slightly dull workshop",

"description": "Dolorem non voluptatem odio maiores minus. Amet nisi est recusandae veniam quasi maxime. Natus alias pariatur eos magni. Hic quo ipsa suscipit voluptas magni Pascal nobis et rerum. "

},

]

}

By default these will then be flattened when stored like this

{

"name": "Matthew",

"lessons.Name": [ "Super amazing session", "Slightly dull workshop" ],

"lessons.Description": [ "Dolorem non voluptatem odio maiores minus. Amet nisi est recusandae veniam quasi maxime. Natus alias pariatur eos magni. Hic quo ipsa suscipit voluptas magni Pascal nobis et rerum. ", "Dolorem non voluptatem odio maiores minus. Amet nisi est recusandae veniam quasi maxime. Natus alias pariatur eos magni. Hic quo ipsa suscipit voluptas magni Pascal nobis et rerum. "]

}

As we can see we now have 2 arrays with a string in each, this might be totally fine for your purpose, but this also means that we no longer maintain the relationship between Name and Description. If we need to maintain that relationship we can update our index mappings, setting lessons to a nested type.

PUT /trainer

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"lessons": {

"type": "nested"

}

}

}

}

These will now be stored as independent objects and maintain their relationship.

Flat

This is when all the data is flattened into a single field, this method is particularly useful when dealing with large amounts of data with unknown fields as this can prevent defining too many fields which can cause memory errors.

However we also want to be careful when using this method as it treats the entire value as keywords which does not provide full search functionality.

We first update our mappings to set the property we would like flattened.

PUT trainer

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"name": {

"type": "text"

},

"information": {

"type": "flattened"

}

}

}

}

In this example we have an unstructured object called information, the payload varies document to document, we want the ability to search over this field, so we decide to store them by flattening the object.

POST trainer/_doc/1

{

"name": "Matthew",

"information": {

"birthday": "2020-02-06",

"firstPetsName": "Fluffy",

"favouriteColour": "Purple"

}

}

When returning our data from source the structure is returned in the same way.

Join

In some situations we may need a parent/ child relationship. These should be used with caution, we are not creating a copy of your database and structure, we are creating a search engine and we want to aim to denormalize as much as possible.

Before using this method take a step back and question how the search will be performed. In most cases I would pick duplicating data over introducing joins.

We have introduced a lead trainer that is responsible for a set of trainers.

PUT trainer

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"trainer_relations": {

"type": "join",

"relations": {

"trainer": "leadTrainer"

}

}

}

}

}

Bob is the lead trainer (with the ID of 1) to Matthew.

{

"name": "Bob",

"trainer_relations":{"name":"leadTrainer"}

}

{

"name": "Matthew",

"trainer_relations":{"name":"trainer","parent":1}}

}

Now searching for all the trainers under a particular lead trainer is easy-

GET trainer/_search

{

"query": {

"has_parent": {

"parent_type": "leadTrainer",

"query": { "match": { "name": "Bob" } }

}

}

}

What about spatial data?

- Shapes

- Points

- Geoshape

- Geopoint

More on these in future posts.

Adding many documents to an index

A particularly useful endpoint when indexing documents is the _bulk endpoint. You may have large amounts of data to index, if we used the above example of putting a single document we would very quickly run out of connections and indexing would take a very long time.

We can send many updates in one request by using the _bulk endpoint.

POST _bulk

{ "index" : { "_index" : "trainer", "_id" : "1" } }

{ "field1" : "value1" }

{ "index" : { "_index" : "trainer", "_id" : "2" } }

{ "field1" : "value2" }

{ "index" : { "_index" : "trainer", "_id" : "2" } }

{ "field1" : "value2" }

On first impression this might look like an array of updates, however it does not have square brackets surrounding it.

When sending a bulk request we first send an object of intent- this will let Elasticsearch know what the operation will be (In this example the first instruction is to index a document in the trainer index with the ID of 1), the second object will then be the data for this request (Similar to the payload when putting a single document).

Hopefully that gives an overview of elasticsearch. Pop over to the repo if you want to play around with any of these concepts, which contains:

- Elasticsearch single node instance setup via docker

- Data generator for students and trainers written in dotnet core

- Configuration

Spin up everything by using the command docker-compose up.

Have fun 🎉🎉

Get the code